By Genot “Winter Elk” Picor

Much has happened since my past journal entry. When our voyageur brigade arrived at the village of d’étroit in August, we discovered the settlement had been burned to the ground. We were told an ember from a baker’s pipe fell into dry straw outside a horse’s stable. The folk of the town could not contain the blaze that quickly spread and consumed the wooden structures. Only Fort Lernoult and two stone buildings survived the inferno. June 11, 1805 was recorded as the day of the tragedy. Fr. Gabriel Richard sought and obtained aid from both sides of the river, be the benefactors American, British, French or Indien.

Law and order had been maintained, and the helpless inhabitants constructed crude dwellings to protect themselves from the elements. Dignitaries and judges had arrived to administer governmental authority, provided for in the Ordinance of 1787. D’étroit was now part of the Northwest Territory. By September, work had begun in earnest and the town commenced to rise from the ashes. Our voyageur brigade was informed by a courier that an agent from The North West Company in Montréal was on his way to assess the furs we had delivered the previous month. If all went well, the small company with which we were employed would be bought by the North West Company. By seasons end, we could expect our pay.

It was also during this time I had first set my eyes on Wenoka of the Outawa (Ottawa). I was much too shy to introduce myself, and not knowing what was customary among her people, I waited for a proper introduction. That introduction would come soon enough.

The governmental authority seated in d’étroit put our muscle to use. We imported supplies near and far to help with the rebuilding of the town. I was continually surprised by the ingenuity of my voyageur brothers. They even transported a harpsichord when asked to do so and without harm or damage to the exterior or interior structure! We were paid fairly for our labors by those who supervised the construction of the village. As always, the boundless energy of Fr. Richard was an inspiration to us all. He made no distinction between race or creed in his efforts to bring relief to the suffering.

By mid-September, commerce was beginning to return to d’étroit. The agent from the North West Company finally arrived. His name was Alexander Frobisher, and he was a nephew once removed from wealthy Montréal fur trader Benjamin Frobisher, a founding member of The Beaver Club.* Frobisher offered his apologies, having been way-laid in Toronto during the August 1, 1805 Indenture of the 1787 Purchase from the Mississauga. We surrendered to him the remains of George Hubbard. If you recall, Hubbard had been struck by lightning while refreshing himself along the shores of Lac Huron. Frobisher assessed the value of furs to be less than what we had anticipated and an argument quickly ensued.

By 1805, the North West Company was culling furs from as far north and west as the Canadian territories. Achille, acting as an agent for the interests of our small company, tried to persuade Frobisher to change his mind. The transportation of furs along the coast from Mackinac to d’etroit took time and money. Should Achille accept his offer, we questioned if we would be paid in full for our services. It seems the owners of our small company might have overvalued the quality of our furs. Negotiations were ongoing.

In the meantime, I learned Wenoka spoke English, French, Outawa and Ojibwa. She was a person of some importance in her community. Her father was Maakwaa Oonce (Little Bear) and her mother was Waaseyaa (First Light From The Rising Sun). To her family and to her community, I was a lowly voyageur of little or no importance. I believe Wenoka’s parents had someone in mind who would be of some status, although she was not betrothed to anyone. Our eyes met only a few times until one day, an unexpected turn of events brought us both together.

Idle hands mean trouble. When we weren’t assisting Fr. Richard or the town officials, we spent our time playing cards, rolling dice and gambling, and we would gamble on just about anything. Mainard bet Devereux he could produce a longer belch after both men had downed an equal amount of hard cider. The men quickly placed their bets, with the voyageurs adding to the pot. Eight gills* of the brew were poured into identical mugs. Both men inhaled several times before the count was commenced…3…2…1. Mainard won the bet, having exceeded Devereux’s belch by at least three seconds. Unfortunately for Mainard, he also belched up his breakfast.

Gautier and François, two other voyagers bet on who could heave a canoe paddle the farthest, by thrusting the object like a spear. The opponents were of good physical health and of nearly equal size, so those of us in attendance could not accurately decide who would be the better contestant. Rules were set down. The men were allowed three steps forward to gain momentum and could not cross a line etched in the dirt. Should either contestant cross the line, that man would be disqualified.

I sat beneath a pear tree after having placed a small wager on Gautier. François began the contest. He stretched and loosened his right arm, rotated his right wrist before gripping the paddle like a lance. He took three long strides and released it, thrusting it in a smooth arch. It landed some distance, about a perch and a half away* from the demarcated line.

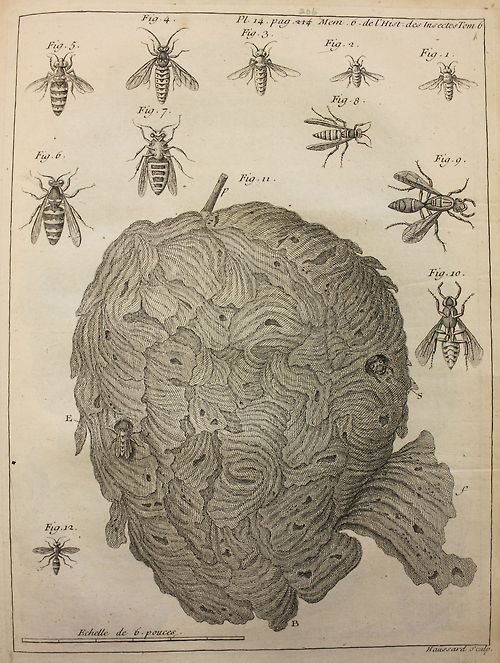

Now Gautier was left-handed, which meant I could see his face as I sat under the shade of the tree. Like his opponent, Gautier stretched his arm and wrist before taking his turn. He took three long strides as did François and released the paddle into the air. But Gautier had stumbled slightly, and his airborne paddle struck a nest of wasps that hung from the same pear tree under which I was seated. The nest exploded into an avalanche of angry yellow and black striped wasps. Pieces of the paper nest, along with the canoe paddle struck me on the back of my neck. The angry, humming swarm engulfed us. Many men from the brigade ran to the river’s edge and submerged themselves in the water. I did the same, flailing my warms wildly, slapping the creatures from my hair before diving into the river. By then, the searing pain from their stings had radiated to my arms and down my back.

The cold water provided some relief. When the threat had disappeared, my mates pulled me from the river. They removed my tunic to reveal six or seven stings that had quickly surfaced into painful welts.The calamity had drawn the attention of Wenoka’s father, Maakwaa Oonce, who arrived in short order. He advised my companions take me to his daughter. She was a healer who belonged to the Midewiwin*. And so it came to be, I was finally given a proper, yet somewhat embarrassing introduction to Wenoka.

Wenoka boiled the inner bark and leaves of a willow tree, which she gave to me to drink. Then, she made and applied a poultice from a fern commonly found in the dense forests and gently applied the balsam to the stings. To protect the poultice, she covered each sting with a moistened and crushed broad-leaf plant*. Soon, I was feeling some relief. I thanked her and felt obliged to continue the conversation.

“How did you learn your skills?” I inquired.

“Healing has been passed on from those who came before us,” she replied.

Wenoka, who had been standing behind me, now sat down and faced me directly.

“Long ago, it was said a plant lived beneath these waters. It was poisonous and caused The People great pain when they went to bathe. The plant felt sorry for The People and called upon the ‘little chiefs’ of the land to council.”

“I wish to give away my bichibowin (poison) so that The People might bathe in peace,” said the plant.

Bee spoke first.

“I can use the poison to protect my hive. I will warn anyone who comes too close before I use the poison, for to do so will cost me my life.”

“I will take some poison and keep it in my tail,” said Wasp. “I will fly close to anyone who threatens my nest before I spear them. Wasp joyfully danced in a circle, shaking its new weapon.”

Rattlesnake was the next to speak.

“I will take some poison too. I will keep it in my mouth. Before anyone gets too close, I will rattle my tail to warn them.”

Finally, a three-leafed vine asked for poison.

“My brothers and sisters of the forest trample me when they hunt and gather. I will take some poison as well. If they crush or burn my leaves, I will release the poison in that way, so then they will know to let me be.”

“Then, Gitchii-Manitou spoke. ‘In all things there must be a balance. I will give the Plant People powerful medicine. They will share their gifts with the healers who will care for The People. The healers will be called Midewiwin.”

She tipped her head to the side, gently smiled and touched my cheek.

“And this how the Midewiwin came to be. You rest and let the plants do their work.”

Wenoka departed from the lodge. I laid face down on soft skins she had spread before me. In the center of the lodge burned an aromatic fire scented with cedar and sweet grass. The smoke rose through an opening in the roof of the lodge and out into the clear blue sky. I was smitten by her gentleness, but I would soon discover there was another side to her.

*The Beaver Club was a gentleman’s dining club founded by fur trading barons of Montréal in 1785. Benjamin Frobisher was a founding member. “

*Eight gills” is the equivalent of one quart. A “perch and a half” is approximately 24 feet in length; one perch is 16 ½ feet long.

*Midewiwin was the name given to the Anishinaabe ‘medicine society.’

*The fern is known as “rattlesnake fern,” and the moistened broadleaf plant is called the “plantain.” The plantain was brought to North America by the first English settlers as a food source and medicinal remedy. It was known as “Englishman’s foot,” or “White man’s foot print.” It was said to grow where ever a white man stepped. It’s analgesic qualities also helped to relieve “plantar/foot” pain. No one is certain when it was first brought to the Great Lakes.

Special thanks to award-winning naturalist Mark Szabo of the National Association for Interpretation and “Mike” from Maple Lane Pest control for their assistance with this story.

The Wasp’s Nest as told by Genot “Winter Elk” Picor from Voyageur Tales © Genot Picor. Published on Voyageur Heritage with permission of the author.